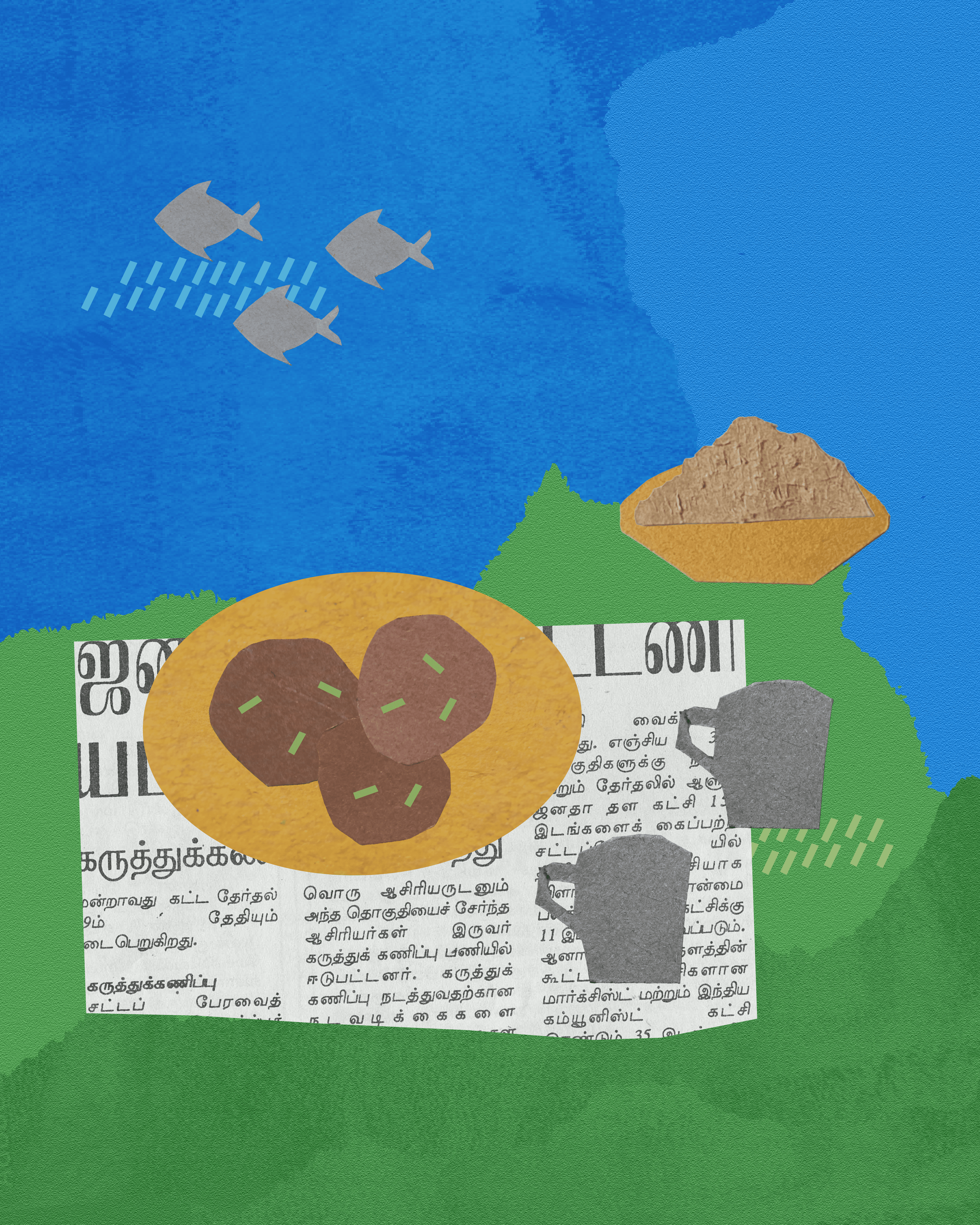

The bright green of the walls looked golden with the sunlight that thickly came from the ventilator shade. It was still dark inside her bed-bound world, still, she is privy to all the sounds of the universe.. Mooma and I heard the fried food seller hawking “Vaada, Vade” strolling outside. The two ‘a’ vaada is a deep fried hat-shaped snack filled with onions, dried fish, coconut scraps, and little masala with an outer casing of moong dal and rice dough. The vade is the popular ‘dal vada’ or ‘parippu vada’ like we call it in Kayalpatnam, the coastal small-town in Tamil Nadu, from where the sound of the hawker originates.

Mooma sitting and holding the handle of her stainless steel mug of “theyilai” (Tamil for tea) said this: manusi de hayathulam ipdiye povudhu. She meant “all her energy is sapped in her own hawking”. In the dialect that we speak, hayath is an Urdu/Arabic word or concept that we Tamil-ise to mean an idea that’s between soul and energy. Or else it is simply the energy of the soul.vwvw

That morning, the air for the next minute was filled with the voice of the vendor woman’s labour until she walked past our house to a distance – faintly receding. Fried food sellers, mostly women, come with their aluminium/plastic creel or tub with neatly cut newspaper bits to wrap the snacks you get. They stop house for house to ask if the family wants to take some. Many households wait with their tea, always made with ginger, cardamom, and sometimes Kaava podi (includes pepper, Indian sarsaparilla, dried ginger, liquorice, and pepper) for the sound of the fried food seller. For many Kayalites, drinking tea without a bite of Vaada or Vade is very undoable. The sound of the vendor is precious in the mornings where you wait to start your day with a bite of this and a sip of that.

Hearing “Vaada, Vade” here in the morning air creates a semiosphere. In the discipline of semiotics that studies signs, sounds, image, and other “signifiers” are elements of communication composed of a physical expression. Like Fabio Parescolli writes in Bite me: Food in Popular Culture, “their (signs like sound and image) life might be shorter, but their temporary interaction with the rest of the communication network is much more intense.” The sound of a Vaada/Vade vendor thus at once becomes part of the air, the semiosphere of Kayalpatnam’s mornings, a synesthesia to drinking tea and starting the day.

Knowledge as labour

In a few minutes, fish vendors in motorcades and by foot, start calling out “Sithi, Sithi”. Sithi as one would assume isn’t the Tamil word for fish. Sithi/Chithi stands for “Aunt”, mother’s younger sister or one’s father’s younger brother’s wife, precisely. The Catholic fisherfolks of the sub-region of Coromandel coast towards the south east in the Thoothukudi district, where Kayalpatnam is, and the Muslims of the same sub-region share a kinship that assumes/believes “children of the brothers and sisters”. The two community people call each other “Sacha, Sithi”. “Sacha” for men, “Sithi” for women. It is to remember through the lexicon of the quotidian that we parted to different paths and faith starting as one. Islam and Catholicism in the region came one after the other, five centuries apart from each other, which splitted the faith of the same community into two and many. This is why the kinship still lingers through everyday fish mongering. The Muslim women respond to this fond call of the fisherwomen and men with fish (It is meen in Tamil for fish) by coming out to their doorsteps or to the alleyways. Cousins of history engage in banter and bargain and quickly sort the transaction. The fisherfolk know the exact fish that would be sold in Kayalpatnam’s streets and do not bring from landing centers the fish that won’t sell. Different kinds of promfrets, kingfish, ladyfish, anchovies, sardines, barracudas are topsellers among Kayalites and the fish vendors only bring these. It is highly improbable that any other fish seller, oblivious to the preferences of these buyers, would be able to sell it in the very same streets as the Catholic fisherfolks.

Mudukku as markets

The street and alleyways that we call Mudukku in Kayalpatnam are spaces that host vendors and voices, sounds of labour, endlessly. Besides built-forms these sounds also give the spaces their character. Mudukku in Kayalpatnam is an all-women space between any two houses or a whole line of houses that run perpendicular to the main streets. Men are strictly admonished if they happen to be found walking around here. This is a boon to women vendors who have access to the household’s side entrances called “Thalai Vasal” and “Thittu Vasal” through Mudukku. Banana sellers, bringing directly from the plantations, Keerai (green leafy vegetables), ghee, milk, sweet potato, tapioca, mookuthi avarai (clove beans), palm root, thennankuruthu (the kernel of the coconut palm that is yielded when a tree is felled), palm fruit, baked foodstuff like biscuits to home-made snacks like Mukkuzhi Paniyam (made with semolina/rice flour, eggs, sugar, ghee, and condensed milk) all reach you through your Mudukku while you idle inside your house. This all-women during day time looks listless but the truth is that women from the surrounding villages and the ones from the very same town see and savour benefits out of this narrow alleyway. It was not intended to be a space for transactions alone. School-going girls to wrinkly grandmothers press their steps over the paths together with the vendors here. It allows women vendors access to privy spaces that male-vendors may not have.

Mudukku is a cornerstone to understanding Kayalpatnam’s spatial and sound world. Other sensorial instances from other cultures to understand the texture and meaning of a Mudukku could be this: the sound of podders’ horns with breads in Goan villages, chaiwalas hawking and walking through the aisle inside the trains, like the clatter of vessels and smell of incense in the mornings at a South Indian breakfast cafe, Mudukku’s sight, smells, and sounds are experiential metonyms to Kayalpatnam alone. Experiential metonyms are plenty in that. How Bombay folks from the South Bombay of yore recall the sound and sight of Dhoodh Puff man or how Chennai’s elders vouch for the Chole masala from Mount Road’s Woodlands or the bright terraces that old-timers from Delhi sing paeans about

Place and labour as language

While this story of labour is tied to a place, set in the corner of the south east coast of India, the phenomenon isn’t. Like Selma Carvalho writes in her introduction of her book The Brave New World of Goan Writing and Art 2025, “the paradox of language is that, while it creates silos it is also responsible for much of the syncretization that we experience in human societies”. Cuisines in that regard are extensions of languages because we speak and eat with our tongues and palates from the same part of our bodies. That’s why it is quickly comprehensible across cultures that immigrants world over actively fold their home’s labour inside their bags, often as foodstuffs, with prayers in the fluttering lips waiting at the security check-ins in airports. In a world that is increasingly eating the same, and food everywhere beginning to taste the same, with retail giants bringing everything from everywhere to everywhere else, why do we still pack bottle masalas, fried onions, bebincas, bamboo shoots, and seeni maavu from one subcontinent to another continent? In this over-saturated globalized world, few forms of culinary labour still couldn’t cross seas and fly mountains. The patience and pain required to hand pound that bottle masala, the slowness of a bebinca’s recipe, the willingness to sit by the hot hearth to sift through a man-sized Chatti of seenimaavu goes beyond the meaning of homeland, community, and heritage.

A good dose of lack of choice consequential of lack of resources has gracefully rested the ornate recipes of embellished microcuisines over the shoulders of a few. Perhaps, that’s why even in this age of hyper-availability and overtly connected markets, people miss places when they think of food – for their sound, smell, and sight. We still don’t have the technology to transport commodities together with their semiotics. One easily finds turmeric roots essential for one’s ritual ornating of Pongal pot from a grocery store in Dubai. But it is not the same as harvesting the root from your backyard in your village in Tamil Nadu. Finding a fine quality hilsa fish in the U.S. is never the same as your Maachbajar shopping in Kolkata. Eating from a franchisee Chowpatty-like-chat in London isn’t, no doubt, like eating from your favourite chaat place in Juhu chowpatty. Food is never the same, singling it out from its setting, ripping it out of its signs.