My relationship with the sun has always been a little complicated. As a kid growing up in Chennai, naturally, like most others, I hated the sun. I was so jealous of the sweater-clad kids on the TV, making snowmen and snow angels.

I also never understood why the women in my family would willingly spend hours in the sun, painstakingly making the best use of the summer sun. Not that it was a scarce resource in Chennai anyway. From the Javvarsi (Sago) vadam to the rice flour and onion vadams, the colorful crunchies were quite common occurrences during the summer. The citron and mango pickles that they would make as if to preserve summer in a jar.

Between poring over magazines, tall cups of moru chilled mangoes, and earthen pots filled with water, summer as a kid was easy. With all our cousins under one roof for the summer, we played, watched TV, read, ate, and slept. But sometimes, we were given the duty of running upstairs and carefully uprooting the soft white dhotis filled with vadams before the surprise summer showers got to them. Sometimes we had to safeguard them from being pecked away by the crows.

Sneaking bits and pieces of these raw vadams was a cheap thrill for us kids.

Different from all these vadams, however, was a pungent smelling dark & dried pellet. It smelled like dry garlic and tasted even worse. Even the crows wouldn’t touch it. Eating the still-drying pellets of it was the worst possible punishment your cousins could give you.

We found bits and bobs of these mysterious black objects in our food which we either pushed to the corner of our plates or preserved in the nook of our mouths and spat out later. I couldn’t get the appeal of it. My grandma would then make black laddoos (balls) of these dried pellets and distribute them to all her daughters, who would then safeguard this prized possession; this was the Vadagam. With different dried dals, shallots, garlic, curry leaves, and a bunch of whole dried spices, vadagam was mainly used either in the beginning or at the end of a dish for “thalippu”/tadka or tempering.

I stood in my mom’s kitchen years later, alone as a freshly minted college graduate back in my home city Chennai. I rummaged through her cupboard (while she was traveling, of course) for dry staples to whip up a quick meal.

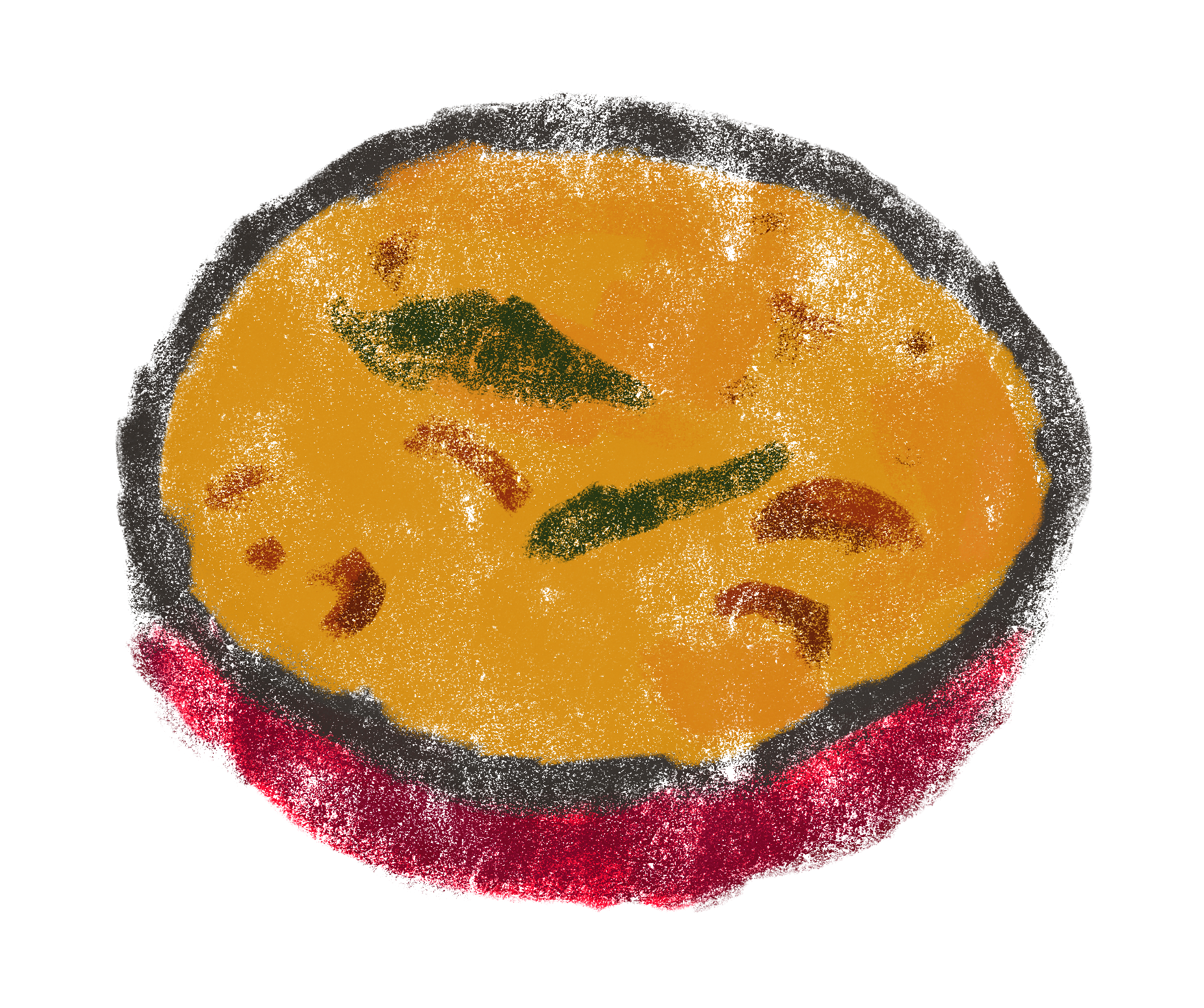

I tried to recreate Amma’s simple thakkali paruppu (Tomato Dal). She sent me detailed instructions with just five ingredients with vague measurements on Whatsapp. One of the ingredients was the vadagam, the same black mystery ball that haunted my childhood summers. Being the straight-A student, I followed my mom’s instructions to the T and ended up making a good paruppu (nothing like the original, but good enough).

Years later, and miles away from home, I would meet the vadagam again. This time in Bologna. At a food art exhibition, I witnessed a Dutch artist at work. She used different textures, colors, and forms of food to make a stellar piece of edible art, which we could then taste. We each scooped a portion of the art into our plates. A green juice made the dish less bland and tepid. I discovered that this green juice was actually “Vadouvan,” the French cousin of the humble vadagam. My humble vadagam. In a very sheepish (and an Indian) way, I felt proud that this was part of one of the most studied cuisines in the world. However, I felt sad for them when I later found that it sells as a replacement for “curry powder.”

I tried to recreate Amma’s simple thakkali paruppu (Tomato Dal). She sent me detailed instructions with just five ingredients with vague measurements on Whatsapp. One of the ingredients was the vadagam, the same black mystery ball that haunted my childhood summers. Being the straight-A student, I followed my mom’s instructions to the T and ended up making a good paruppu (nothing like the original, but good enough).

The flavor that the vadagam brought to this was unparalleled. I fell in love with the vadagam again. It became a loyal part of my limited culinary repertoire.

Years later, and miles away from home, I would meet the vadagam again. This time in Bologna. At a food art exhibition, I witnessed a Dutch artist at work. She used different textures, colors, and forms of food to make a stellar piece of edible art, which we could then taste. We each scooped a portion of the art into our plates. A green juice made the dish less bland and tepid. I discovered that this green juice was actually “Vadouvan,” the French cousin of the humble vadagam. My humble vadagam. In a very sheepish (and an Indian) way, I felt proud that this was part of one of the most studied cuisines in the world. However, I felt sad for them when I later found that it sells as a replacement for “curry powder.”

A confluence of the streets of two cities, Chennai and Bologna

I happily gave bits of the vadagam that I had with me to my curious food-loving friends. An Italian friend of mine even treated me to a buttery pumpkin risotto on a beautiful sun-lit afternoon terrace where the soffritto included; you guessed it: the vadagam.

From stir-fries to dals to soups, I threw it in everything if I felt something was a little amiss. Was the vadagam flavorful and nutty? Yes. Did it elevate any simple dish with just a few ingredients? Yes.

But that’s not my favorite part about the vadagam.

The unique part about the vadagam was the convenience of this brilliant little spice medley. All my aunts would continue to use these vadagams for the entire year until the following year. It was great in dal-based dishes, tamarind-based broths, or even simple vegetable stir-fries.

Some say the vadagam originates from the Chettiar community of yesteryear traders and merchants who were adept travelers and always took some handy, convenient foods with them wherever they went. But here, it wasn’t used by the traveling merchants. Instead, it was for the ease of use for housewives and home cooks. Convenience - an act that is questioned and scrutinized when women cook.

“All these kitchen gadgets he buys for her, then what’s the effort in cooking?” I would overhear my grandma complaining about my mother as if she expected my mother to renounce all of this and spend hours together toiling. “Oh, shortcut ah? Oh, from the fridge, ah?”

![]()

God forbid my mom to serve some reheated sambar to my relatives. They would die from the shock rather than from food poisoning. This vadagam, to me, was a slap on their faces. The vadagam helped the women save a lot of time and effort, the time they would take in frying onions or in, mincing up the aromatics, or grinding the spices. For my mother, the vadagam was her mother’s hand over to her as a 20-something young bride who was whisked off to Ahmedabad, where she didn’t speak the language.

The vadagam was the saving grace when my mother had no interest in cooking but still had to whip up a 3-course meal for the ever ungrateful extended family. The vadagam was forgiving and understanding, perhaps more than the family she called her own after marriage.

From stir-fries to dals to soups, I threw it in everything if I felt something was a little amiss. Was the vadagam flavorful and nutty? Yes. Did it elevate any simple dish with just a few ingredients? Yes.

But that’s not my favorite part about the vadagam.

The vadagam, to me, was the epitome of convenience. Unlike the other special sun-dried foods, the vadagam didn’t feature on the menu. It was shy to take up space and often went unnoticed and unappreciated, like the women who made it.

The unique part about the vadagam was the convenience of this brilliant little spice medley. All my aunts would continue to use these vadagams for the entire year until the following year. It was great in dal-based dishes, tamarind-based broths, or even simple vegetable stir-fries.

Some say the vadagam originates from the Chettiar community of yesteryear traders and merchants who were adept travelers and always took some handy, convenient foods with them wherever they went. But here, it wasn’t used by the traveling merchants. Instead, it was for the ease of use for housewives and home cooks. Convenience - an act that is questioned and scrutinized when women cook.

“All these kitchen gadgets he buys for her, then what’s the effort in cooking?” I would overhear my grandma complaining about my mother as if she expected my mother to renounce all of this and spend hours together toiling. “Oh, shortcut ah? Oh, from the fridge, ah?”

God forbid my mom to serve some reheated sambar to my relatives. They would die from the shock rather than from food poisoning. This vadagam, to me, was a slap on their faces. The vadagam helped the women save a lot of time and effort, the time they would take in frying onions or in, mincing up the aromatics, or grinding the spices. For my mother, the vadagam was her mother’s hand over to her as a 20-something young bride who was whisked off to Ahmedabad, where she didn’t speak the language.

The vadagam was the saving grace when my mother had no interest in cooking but still had to whip up a 3-course meal for the ever ungrateful extended family. The vadagam was forgiving and understanding, perhaps more than the family she called her own after marriage.